Written by Lucas Smith

Brendan Hughes was one of the most active members of the Provisional I.R.A. at the height of The Troubles. He functioned as a literal soldier for the cause, an organizational commander planning operations and leading them with a rifle in hand. This role in the organization is worthy of analysis, particularly when examined comparatively beside other leaders within the group. Comparative analysis with Gerry Adams in particular offers insight into the boundaries between the grand-scale strategist role and the operational agent role within such an organization. That analysis also stands to demonstrate the vital relevance of such a boundary when the ideology of the latter remains stable but that of the former evolves and shifts. Given the nature of armed resistance, it comes as no surprise that these two distinctive roles so frequently emerge. Both are necessary to the function of such an organization, and they often work in marked complement, but their divergence can be fraught – especially regarding the interpersonal relationships of those filling such roles and as the organization and its goals evolve.

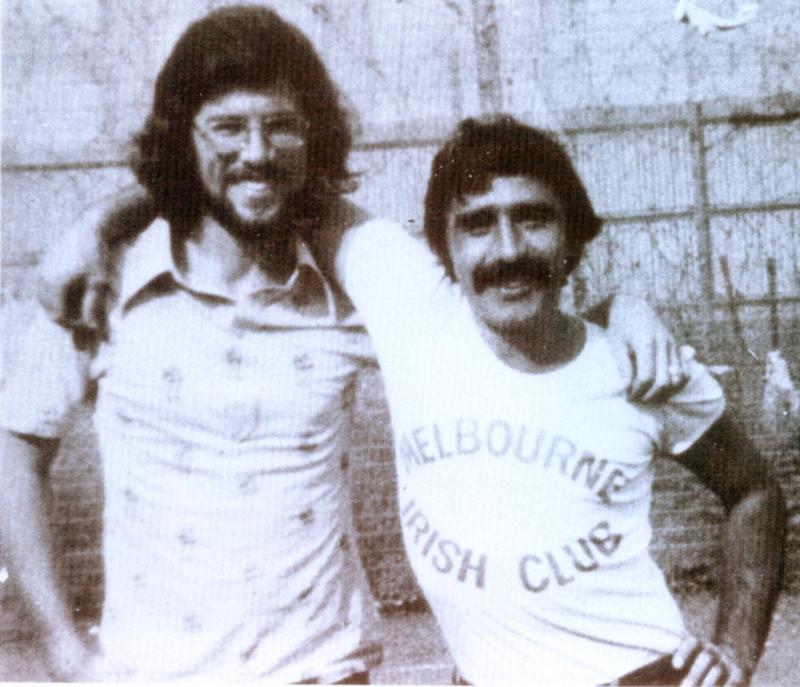

The image above shows Adams and Hughes grinning from within the barbed wire fences of Long Kesh prison. This photograph provides a visual representation of the solidarity of these two men, two men who were described to be as close as brothers (Keefe, 77-78), working in their distinct yet complementary roles to further their cause. Their comrade Dolours Price joked that she never saw Adams with a gun and she never saw Hughes without one, but at the height of the Troubles this dynamic functioned very effectively for the two and for the Provos. Adams said of Hughes that he, “‘compensated for any inability to articulate politically at great length by doing the right things instinctively’” (Adams, as quoted by Keefe, 77) and Hughes himself saw himself as an instrument of the cause – if an agent of violence, an agent nonetheless, an instrument with a clear purpose. The primary issue of this boundary between the roles came when the instrument was left without this clear purpose and thus discarded.

As the Provisional I.R.A. evolved through the course of the Troubles, the leadership, particularly Gerry Adams, increasingly set their sights on greater political action. The “Armalite and the ballot box” strategy increased their involvement in democratic political channels and the eventual advent of Sinn Féin provided them a legitimate political operational platform. As the tides increasingly turned towards peace, the physical force practices of the Provos markedly decreased and became far less mainstream. This shift, of which Gerry Adams was at the head, left Hughes, the soldier, profoundly disaffected. Gerry Adams became the political leader of Sinn Féin and disavowed any previous I.R.A. involvement.

Late in life, Hughes openly criticized Adams and the organization’s direction. He stated in his Boston College interview, “what the I.R.A. and Sinn Féin have done is just become another middle class party and dropped all the important things that we fought and died for, mainly the enhancement and the betterment of the working class people in Ireland” (Segment 9, 1:22). Hughes addresses an important consideration of class here, one often overlooked in the context of a struggle based in numerous other sociopolitical factors. Furthermore, Adams’ disavowal of the I.R.A. upon his leadership of Sinn Féin deeply upset Hughes in that it transferred all moral accountability for the deeds done onto Hughes and fighters like him – what presumably was taken as an acute indignity from a man formerly so nearly a brother. Hughes had spent almost his entire adult life as a soldier in this war and in his final years, feeling the bitterness of an agent cast aside and a friend disowned, his health declined, at the same time as Adams continued his party leadership and politicking. When Hughes died in 2008, he had wanted no involvement of Adams, Sinn Féin, or the Provos in his funeral. Adams did attend, and when he briefly stepped in as a pallbearer, the photo opportunity was not missed. Terry Hughes, Brendan’s brother, commented in his interview for the Voices from the Grave documentary that it is true that Adams, as he himself stated, did attend out of respect. He continued in remarking that he should have come out of respect, as Brendan played a significant role in his war and, “somebody has to make the war for you to be a peacemaker” (Segment 9, 6:08). This impactful insight from Brendan Hughes’ surviving brother offers a compelling summary of this fraught boundary of roles.

Works Cited

“Brendan Hughes.” longkesh.info. July 13, 2006. http://www.longkesh.info/2006/07/13/brendan-hughes-ending-the-1980-hunger-strike/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

“Gerry Adams, 2014.” Encyclopædia Britannica. October 2, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gerry-Adams/images-videos. Accessed November 22, 2020.

“Gerry Adams, right, helps carry the coffin of Brendan Hughes in west Belfast in 2008.” The Guardian. May 1, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/may/01/brendan-hughes-ira-gerry-adams-sinn-fein-jean-mcconville. Accessed November 22, 2020.

“Gerry Adams and Brendan Hughes in Long Kesh.” Belfast Telegraph. July 21, 2017. https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/opinion/news-analysis/q-how-do-we-know-gerry-adams-tried-to-break-out-of-long-kesh-a-he-wrote-about-it-35952598.html. Accessed November 22, 2020.

Hughes, Brendan. As quoted in Voices from the Grave. “Voices from the Grave – Documentary.” Boston College Subpoena. Video Segments 1-9. https://bostoncollegesubpoena.wordpress.com/supporting-documents/voices-from-the-grave-documentary/#vog. Accessed November 23, 2020.

Keefe, Patrick Radden. Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland. New York, NY. Anchor Books. 2019.