By Grace Lawrence

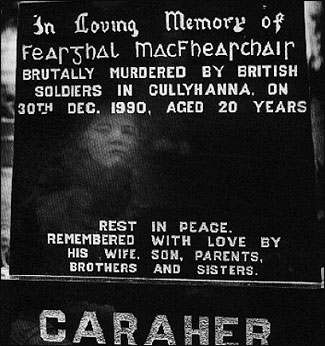

A major problem during the Troubles was the fact that the media played such an important role, but was also incredibly biased. It is seen throughout the book Say Nothing that the IRA had their reporters and news outlets while the British had other reporters and news outlets. More often than now the media was censored in Northern Ireland and the lives lost due to violence during the Troubles never made the news. An article regarding the media censorship tries to set up if something like this happened in the US. Author Ed Moloney states that “In a country with as strong a First Amendment tradition as the United States, most journalists [here] would probably find it impossible to imagine such a thing happening in their own country or in any advanced Western democracy.” In addition, Moloney explains that “thanks to the peace process in Northern Ireland the government in Dublin eventually dismantled the censorship laws in a move designed to edge the Provisional IRA and its political wing Sinn Fein into constitutional politics. Not long afterwards the British government abolished its own censorship regulations, and for the first time since 1976 coverage of events in Northern Ireland was officially untrammeled by state interference” (Moloney). One convenient thing about this being lifted during the peace process was that Britain was able to essentially able to get away with murder in Northern Ireland and hide the atrocities that they committed during the Troubles. In fact, “the Irish peace process has triggered a debate about the behavior of Britain and Ireland during the Troubles, particularly in regard to the way the actions of the police and military forces may have worsened the conflict” (Moloney).

Unfortunately, censorship is not a new tactic in Ireland and Britain. In fact, “censorship has a long if not very honorable place in Irish history” with the British controlling the press “during the 1919-21 war of independence, as did the pro-Treaty side in the subsequent Irish civil war” (Moloney). Censorship was also not only being carried out in the North. “In the South of Ireland it took a less political and more religious form. The state censor was allowed to ban books and films on moral grounds” (Moloney). In an interview with Dr. Geraldine Smyth, of the Irish School of Ecumenics, she states “that with the BBC and UTV, which were the main British channels at the time, reporting was pretty heavily biased toward the British government policy and towards censorship of paramilitary groups” (DeVaney). She also states that during the peace process “there was less bias and more attempt to actually get behind the peace process, to take the referenda seriously that were conducted post-Good Friday Agreement” (DeVaney). While media coverage and censorship was a major problem during the Troubles, it seems that both Britain and Ireland are working toward a more inclusive approach to media coverage.

References:

DeVaney, H. (2014, April 4). Media Ethics In The Northern Irish Peace Process. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from http://www.emergencyjournalism.net/media-ethics-in-the-northern-irish-peace-process/index.html

Keefe, Patrick Radden. Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland. Doubleday, 2019, pp. 223-348.

Moloney, E. (2014, March 17). Media Censorship During ‘the Troubles’. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://niemanreports.org/articles/media-censorship-during-the-troubles/