The Irish Famine (1845-1852) resulted in the deaths of approximately one million Irish people and the immigration of an additional one million. Although Irish immigrants relocated to places across the English-speaking world, including Britain, Canada, and Australia, Irish immigrants to the United States played a key role in mid-century politics. Irish-American communities grew in places such as New York, Chicago, and Boston and exhibited strong influence on urban politics, culture, and geography. In Say Nothing, Keefe alludes to this wider historical process in describing Boston College as an institution founded to serve Irish immigrant families and commented to maintaining “close ties to the old country” (Keefe, p. 1).

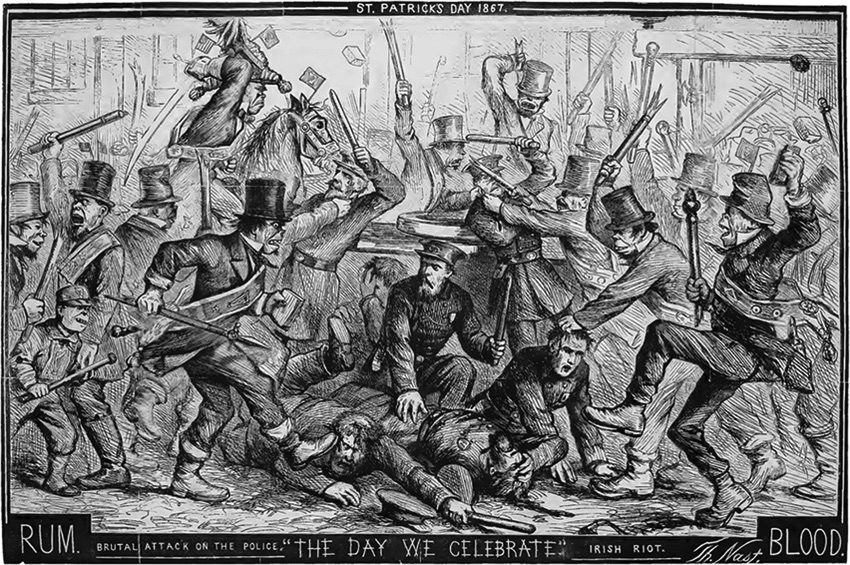

Irish immigrants often faced discrimination in American cities due to religion, ethnicity, and poverty. Anti-Irish stereotypes followed immigrants to the United States and presented the Irish as physically different and culturally inferior. Thomas Nast’s 1867 engraving, “The Day We Celebrate” is a good example. In it, Irish men with ape-like features are depicted engaging in senseless violence against New York City police during a St. Patrick’s Day parade; the lower captions of “Rum” and “Blood” draw on familiar stereotypes about Irish intemperance and violence. On one level, the image reiterates anti-Irish stereotypes, but is it also important to note that it contains an important political message as well. The contrast between the forces of law, order, and civility (the police) and lawlessness, disorder, and incivility (the Irish) suggests that these immigrants pose a threat to the fabric of society. This is an important theme in the history of Irish immigration, as emphasized in secondary sources such as Tyler Anbinder’s City of Dreams (especially chapter 14).

Urban institutions like Boston College can be understood as a product of and a response to this historical experience. Irish immigrants experienced discrimination and segregation in American communities and often had to create separate social institutions, including banks, social clubs, and educational institutions. The Irish Emigrant Savings Bank, for example, served Irish immigrants in New York City and played an important role in moving money from Irish communities in the United States back to Ireland (Anbinder, City of Dreams, p. 238). Similarly, the Ancient Order of Hibernians (founded in 1836) established fraternal lodges across the United States. In an era where Catholics were excluded from other fraternal orders such as the Freemasons, the AOH provided an important social institution for Irish men. The AOH also helped preserve a particular sense of ethnic identity; even today, the organization stresses its historical role in protecting “the clergy and churches from the violent American Nativists who attacked Irish Catholic immigrants and Church property” (https://aoh.com/about-the-aoh/).

Boston College connects to Irish immigrants in similar ways. Along with other Jesuit institutions such as Fordham University in New York, and Loyola University in Chicago, the university was partially intended as a home for Irish Catholic men who were excluded from other institutions of higher learning. Boston College in particular maintains a strong sense of its Irish roots, as evidenced in its role in creating and preserving the Belfast Project.